Echoes of Encounter

Motuarohia Island and the Dawn of Collision Pt 1

I landed on Motuarohia Island, or Roberton Island, as it’s been called since the 1840’s after a choppy flight from Russell, though it is high summer. Oh, it rains here, it pours with a relentless sub tropical weight of cloud, that soaks you to the bone and blurs the horizon (still warm though). From the vantage point on my host’s decking, perched atop a lush lawn that slopes toward the cliffs, other islands drift in and out of view through the northerly mist. Far below, a pod of dolphins leaps and plays in the turquoise waters, their arcs a reminder of the spirit of this place.

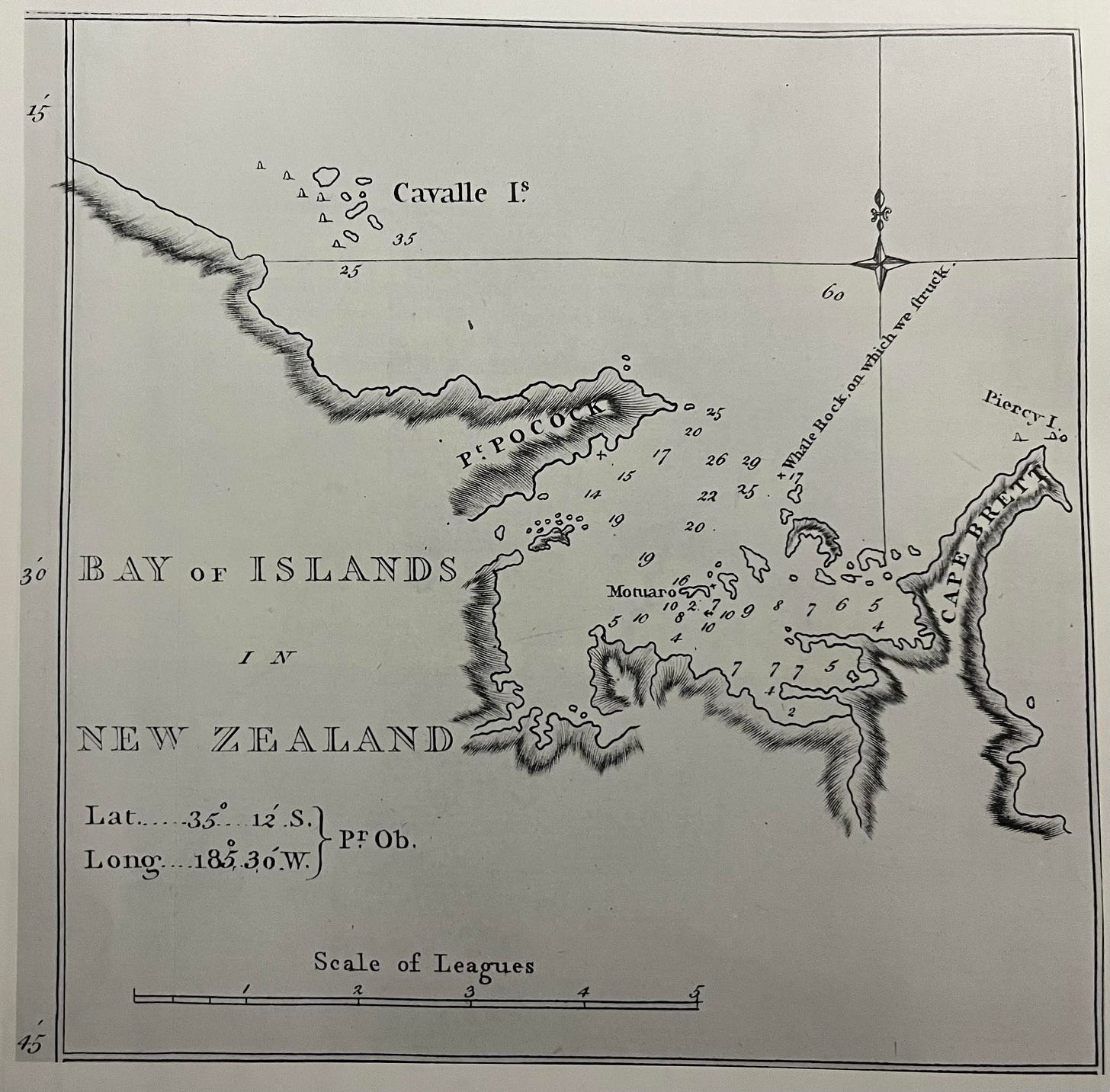

The island may be small, just a speck in the vast Bay of Islands, but it hums with history, a history of first meetings, misunderstandings, bloodshed, tragedy and the irrevocable changes that followed. As I stand there, gazing out, I couldn’t help but reflect on how this serene spot was once the stage for more than one of the pivotal encounters in New Zealand’s story: Firstly Captain James Cook’s landing in 1769. You can see where he anchored from where I stand.

Motuarohia, known to Maori as the “reconnoitred island,” sits in Te Pēwhairangi, the Bay of Islands, a labyrinth of over 140 isles in Northland. It’s a place of stunning natural beauty, twin lagoons of crystal-clear water, dramatic coastal cliffs, and ancient pā sites where Māori once fortified their homes. Archaeological evidence reveals human settlement stretching back centuries: terraces, pits, and defensive structures speak to a thriving community.

In 1769, when Cook’s HMS Endeavour anchored just beneath where I stand, in what’s now Cook’s Cove, the island hosted 200 to 300 Māori, living in harmony with the land and sea. But this idyll was shattered by the arrival of Europeans, marking one of the first significant clashes between worlds. Today, the island is part recreation reserve under the Department of Conservation, part private land, with upgraded tracks revealing its historical layers, a nod to the Tuia 250 commemorations in 2019, which marked 250 years since Cook’s visit.

Cook’s voyage was no mere adventure; it was a mission of Enlightenment precision. Commissioned by the Royal Society, alongside the Admiralty’s secret orders to seek the mythical Terra Australis, Cook and his naturalist Joseph Banks were bound by scientific rigour. Accuracy was paramount, their logs and journals were to be meticulous records of geography, flora, fauna, and peoples encountered. This wasn’t piracy or plunder; it was empirical exploration, with Banks funding his own team of artists and scientists. Sydney Parkinson, the young Scottish draughtsman, was tasked with illustrating the wonders they found, his sketches capturing the exotic in vivid detail. Yet, for all their objectivity, these accounts carry the biases of 18th-century Europeans: a mix of curiosity, superiority, and occasional fear.

On November 29, 1769, after navigating New Zealand’s coast, Cook anchored off Motuarohia. His journal entry paints a tense scene: “I went with the Pinnace and yawl Man’d and Arm’d and landed upon the Island accompan’d by Mr Banks and Dr Solander. We had scarce landed before... we were surrounded by 2 or 3 hundred people, and notwithstanding that they were all arm’d they came upon us in such a confused Stragleing manner that we hardly suspected that the[y] meant us any harm.”

The Māori performed a haka, the war dance, and attempted to seize the boats. Cook, ever the pragmatist, fired a musket loaded with small shot at one of the leaders, followed by Banks and others. The islanders dispersed only after the ship fired overhead. Cook noted he “avoided killing any one of them as much as possible,” wounding just one or two. Peace was restored the next day, with trade ensuing, fish for cloth and nails. Cook described the pā at the eastern tip, admiring the Māori’s fortifications and agriculture.

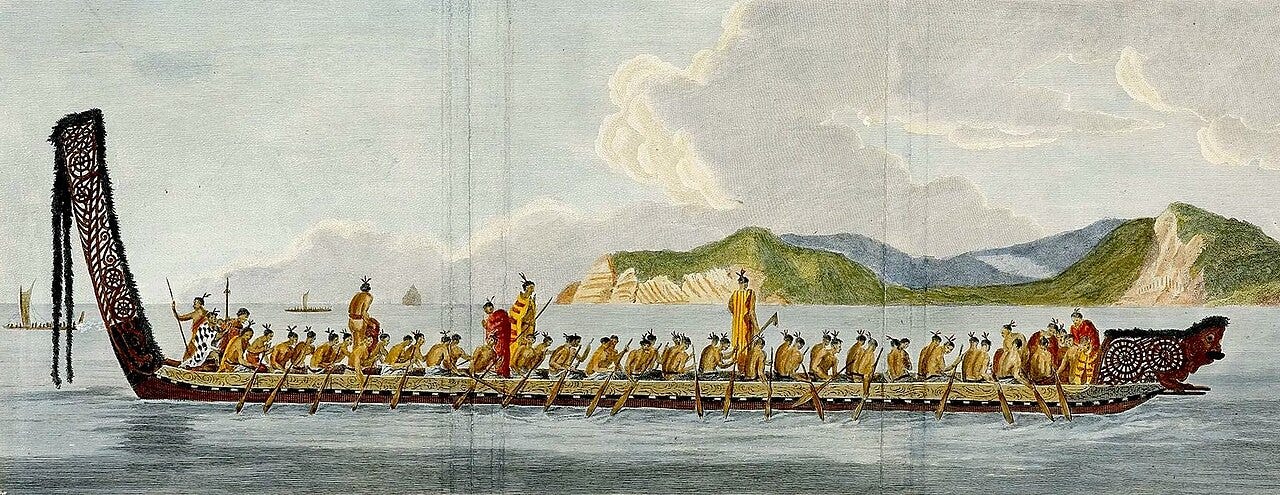

Banks’ journal echoes this, but with a botanist’s eye for detail. He described the island as part of a “most spatious and well sheltered” bay, teeming with life. The encounter unfolded dramatically: surrounded by armed Māori, Banks fired alongside Cook, noting their “war dance” and the chaos. Yet, he marvelled at their canoes and tattoos, viewing them through a lens of anthropological fascination. Banks, like Cook, emphasised the eventual amicability, crediting Tupaia, the Tahitian navigator aboard, whose Polynesian tongue bridged the language gap. Tupaia’s role was crucial; his understanding of Māori dialect, related to Tahitian, likely turned hostility to hospitality, with food and water exchanged.

Parkinson, though not journaling as extensively, immortalised the voyage through art. His sketches from the Bay of Islands include Māori warriors, canoes, and landscapes, capturing the raw humanity of the encounters. One drawing, possibly inspired by Motuarohia, shows Māori in war canoes, their expressions fierce yet dignified. Parkinson’s work, published posthumously (he died en route home), provided Europe with its first visual glimpses of these “new” peoples, fuelling Romantic imaginations. His accuracy, demanded by the Royal Society, ensured these images weren’t mere fantasies but grounded observations.

From the Māori side, the story is one of intrusion and resilience. Oral histories, passed down through generations, frame Cook’s arrival as a portentous event. In Te Pēwhairangi, the bay named by ancestors long before Cook dubbed it “Bay of Islands,” the Endeavour’s appearance was ominous. Local hapū, likely Ngāpuhi, saw the ship as a strange waka (canoe) or perhaps a floating island. The initial skirmish stemmed from defense of territory; the haka was a challenge, not unprovoked aggression. Gunfire was a shocking novelty, “thunder from the gods,” some traditions recall – scattering the warriors but leaving a legacy of wariness.

Modern Māori renditions amplify these voices, countering Eurocentric narratives. During Tuia 250, events on Motuarohia highlighted dual perspectives: Cook’s “discovery” versus Māori’s enduring sovereignty. Artists like Greg Semu reimagined encounters in photographs, portraying Māori as central figures, not peripherals. Paul Tapsell, a Ngāti Whakaue scholar, emphasises the cultural protocols ignored by Cook: no proper karakia (prayer) or whaikōrero (speech) preceded the landing, escalating tensions. Tina Ngata’s work critiques colonial fictions, urging a “Kia Mau” (hold fast) to Māori truths. These renditions portray Cook not as hero but harbinger of colonisation, disease, and land loss.

The differences are stark. European accounts, bound by Royal Society mandates, prioritise factual detachment: measurements, descriptions, minimal emotion. Cook and Banks saw Māori as brave but primitive, their society intriguing yet inferior. They noted cannibalism rumors but focused on trade and navigation. Māori perspectives, oral and holistic, embed the event in whakapapa (genealogy) and whenua (land). The encounter disrupted mana (prestige); gunfire symbolised unequal power. Modern views highlight this asymmetry: Cook’s “small shot” versus the cultural upheaval that followed, treaties and wars.

One telling incident was when three of the ship’s company broke into a garden and stole potatoes (actaully kūmara a native sweet potato). Cook’s report of the incident shows that he did not regard the Maori as inferior (in law).

“For this offence I ordered them to be punished with twelve lashes, after which two of them were discharged; but the third, insisting that it was no crime for an Englishman to plunder a native plantation, though it was a crime of a native to defraud an Englishman of a nail, I ordered him back into his confinement, from which I would not release him until he had received six lashes more”.

The problem lies when one account is oral history, and wrapped about with folkloreistic belief system, and the other is almost peak Enlightenment. There are for example information boards on the island suggesting that the haka, performed by the Maori, was not a threat or a challenge, but one of welcome. That is possible but unprovable, but being surrounded by 2-300 armed men, who were pressing upon the small shore party, and with attempts to steal the ships boats, Cook understandably regarded the Haka not as welcome, but a threat. Even so, when finally he decided the situation was critical he first shot to warn and only reluctantly to harm,

“”In this skirmish only two of the natives were hurt with small shot, not a single life was lost, which would not have been the case if I had not restrained the men who, either through fear or the love of mischief, showed much impatience to destroy them as a sportsman to kill his game”.

Of the two injured one was Otegoowgoowu (Otekuku), the brother of the chief, who Cook assured would not die as it was a light clean wound - though he did say that the ships cannon would bear down upon the Maoris if their was a subsequent attack. There was no follow up attack and gifts were exchanged.

Yet, there’s nuance. Both sides sought understanding. Tupaia’s mediation shows shared Polynesian roots; trade resumed, hinting at mutual respect. Cook admired Māori ingenuity, Banks their botany knowledge. Māori oral histories acknowledge the visitors’ curiosity, even if laced with suspicion. They blame Cook for not knowing the traditions and thus being at fault.

Modern interpretations give this encounter a far more portentous meaning than it should bear, because it is seen as the harbinger of colonisation. But it is hard to see a short encounter like this as being able to carry that moral weight. It was scientific and exploratory, rather than exploitative. Cook was not Cortez, and intention matters.

Standing on Motuarohia today, amid the rain and dolphins, one feels the weight of these layers. This island isn’t just a postcard paradise; it’s a reminder of how worlds collided, birthing modern Aotearoa. As we grapple with reconciliation, renaming places, teaching dual histories, Motuarohia stands as a bridge. Cook’s legacy, scientific triumph though it was, must be viewed through both lenses: the Enlightenment’s gaze and sheer physical courage, and Māori’s enduring spirit. Only then can we honour the full story, rain-soaked and resilient.

The example of Cook punishing his men is such a good illustration of how important formal equality under the law is. Refreshingly detailed, impartial and elegantly written! Can’t wait for more.

A wonderful piece that proves there are always two sides to every story. It's a shame that the zealots who try and shame Britain for our colonial history, never let the facts get in the way of a virtue-signalling cause.